April 9,

1948, release date

Screenplay

by Jonathan Latimer

Based on

the novel The Big Clock by Kenneth

Fearing

Music by

Victor Young

Edited by

LeRoy Stone, Eda Warren

Cinematography

by Daniel L. Fapp, John Seitz

Ray Milland as George Stroud

Charles Laughton as Earl Janoth

Maureen O’Sullivan as Georgette

Stroud

George Macready as Steve Hagen

Rita Johnson as Pauline York

Elsa Lanchester as Louise Patterson

Harry Morgan as Bill Womack

Harold Vermilyea as Don Klausmeyer

Dan Tobin as Ray Cordette

Richard Webb as Nat Sperling

Elaine Riley as Lily Gold

Luis Van Rooten as Edwin Orlin, a

reporter

Bobby Watson as Morton Spaulding

Lloyd Corrigan as Colonel Jefferson

Randolph aka McKinley (radio actor in the bar)

Frank Orth as Burt

Margaret Field as the second

secretary

Noel Neill as an elevator operator

Al Ferguson as the guard

Distributed

by Paramount Pictures

Produced

by Paramount Pictures

The first time I saw The Big Clock several years ago, I

wondered if it were really a film noir, probably because of the film’s many

humorous touches. Ray Milland’s onscreen presence frequently exudes warmth and

joviality, and the wonderful character of Louise Patterson, played by Else

Lanchester, provides many humorous touches. Her abstract sketch of the murderer

is just one example.

But then I heard that

No Way Out, released in 1987 and starring Kevin Costner, is a remake of The

Big Clock, and I thought: I need to see both films again. (Another remake

is a 1976 French film called Python 357, which I haven’t seen.) No

Way Out seems to be in heavy rotation lately on non-major-broadcast

stations, but I have never seen it from beginning to end. Still, it seemed much

more suspenseful than what I remembered from my first viewing of The Big

Clock. How could the two films be based on the same book? I decided to find

out, and I started with The Big Clock. (I have to admit that I have not

yet read Kenneth Fearing’s book of the same name: another book on my reading

list!)

The

opening credits in The Big Clock appear over two still shots, one of

magazine covers that bleeds into a longer one of a sundial. The sundial, it

turns out, is the murder weapon in the story that follows. After the credits finish rolling, the camera pans part of

the New York City skyline. Then it seems to track right into the offices of

Janoth Publications. I wondered if this was a new camera technique, one probably

made easier with new technology after World War II (the film was released in

1948).

The camera now

appears to be on the second floor of the building, but it is empty. Then George

Stroud, played by Ray Milland, steps off the elevator and checks out his

surroundings. Milland’s

voice-over explains what he is thinking in this opening sequence. When he realizes that a security guard is heading his

way, he hides behind a pillar. The security guard doesn’t see Stroud, so Stroud

continues on his way to what he calls “the big clock.” Earl Janoth, head of

Janoth Publications, likes clocks because he values, above all else,

punctuality and productivity. The big clock is Janoth’s idea: It is a

sightseeing feature for tourists who come to visit Janoth Publication, so it

makes money and keeps employees punctual. Inside the workings of the big clock,

George Stroud says/thinks

that, thirty-six hours ago, he was a “decent, respectable, law-abiding

citizen.” And the film then cuts to a flashback.

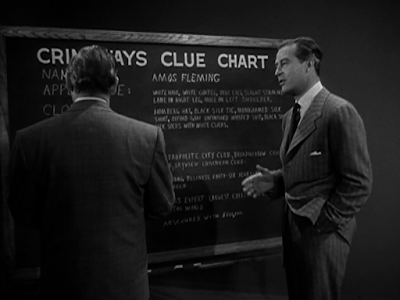

Thirty-six

hours earlier: George is busy at the office. He is the senior editor for Crimeways

magazine, one of many magazines published by Janoth Publications, and he has

just finished producing a successful article that will beat all his competitors

to publication. One of the secrets to George’s success is his Crimeways Clue

Chart, which he uses to track relevant and irrelevant details about everything

and everyone that could be the subject of a magazine feature. He thinks no clue

is unimportant, and it’s a strategy that works for him because he often gets

stories to press ahead of everyone else.

George’s

vacation is due to start the following day, and he and his wife Georgette are

overdue for a honeymoon (they already have a young son). His wife and son don’t

believe that the whole family will actually go on the vacation that they have

planned because George’s work has interfered with his family life in the past.

The film

cuts to Steve Hagen, Earl Janoth’s assistant, addressing a business meeting

about the need to increase magazine circulation. The Janoth company has

recently experienced a 6 percent recession. Janoth enters the meeting room,

acting like the ruling despot of his publishing company, so the conflict in

George Stroud’s life is made pretty clear from the start. It isn’t long before

Janoth uses George’s latest success against him: Research another story that

Janoth wants published or George is out of a job.

Pauline

York is Earl Janoth’s mistress. Her visit to his office doesn’t go as well as

she had planned. She wants more money for singing lessons than Janoth is

willing to give. She approaches George Stroud in a bar while George is waiting

for his wife and pitches the idea of writing an exposé about Janoth. George

isn’t enthusiastic about the idea, but because he just had a disagreement with

his wife about their vacation plans, he allows himself to be distracted by

Pauline long enough to get drunk and visit several night spots around town. One

of their stops is a secondhand shop, where he buys a Louise Patterson original

painting, with the artist herself trying to outbid him.

(This

blog post about The Big Clock contains some spoilers.)

George

and Pauline spend an innocent night on the town, and the only reason that

George ends up in Pauline’s apartment is because of the amount of alcohol he

consumes. While George is still trying to recuperate from the previous

evening’s events in Pauline’s apartment, Janoth shows up for a visit. George is

forced to leave by another entrance, and Janoth sees him from a distance

without recognizing him. Janoth enters the apartment, and he and Pauline argue.

Janoth kills Pauline in a fit of rage with the sundial that she and George had

picked up the previous evening in a bar called Burt’s Place.

Janoth

goes to Steve Hagen and admits to accidentally killing York. Hagen convinces

Janoth not to go to the police. Hagen instead goes to Pauline’s apartment and cleans

up the murder scene: He finds Janoth’s hat, resets a broken clock, goes through

Pauline York’s purse and takes out the handkerchief that George Stroud had

given her to dry herself after spilling a drink on her, and finds the sundial

(the murder weapon). He turns the sundial upside down and reads the bottom:

“Stolen from Burt’s Place, 988 Third Ave.”

After Janoth

tells him that he saw someone outside Pauline’s apartment, Hagen devises a plan

to find out the identity of the person and place the blame for Pauline’s murder

on him or her. He enlists the aid of George Stroud. Hagen doesn’t want Stroud

to know why he is conducting his investigation, but Stroud knows, of course,

because he was with Pauline on the night that she was murdered. Once again,

Stroud’s success causes him misery, this time with even more dire consequences.

He is now forced to use his investigative talents and his Crimeways Clue Chart—to

hunt for himself! The remainder of the film follows the investigation and George

Stroud’s efforts to stay one step ahead long enough to clear his name.